Quick Guide: Male alternative reproductive tactics

Abstract

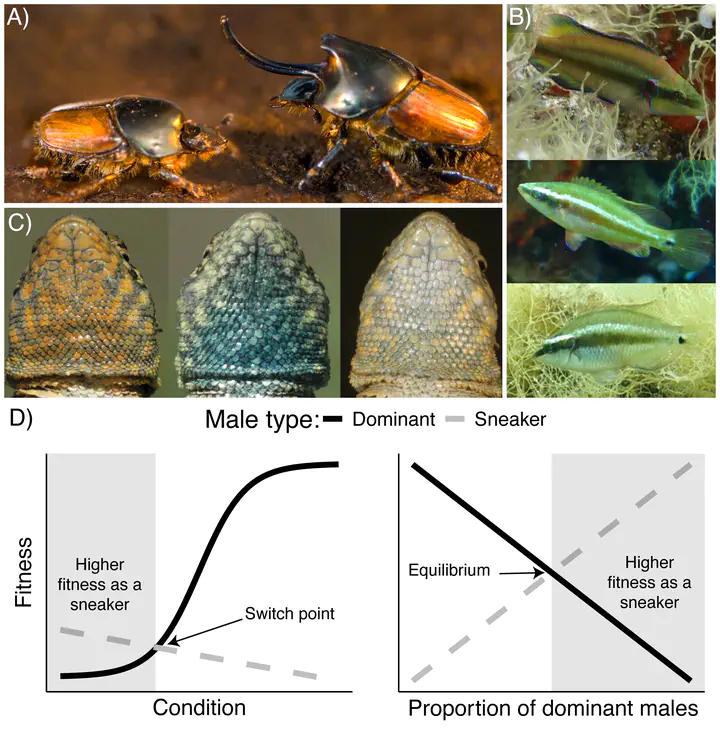

Kustra and Alonzo introduce the reader to ‘alternative reproductive tactics’, in which individuals in a population, usually males, adopt different phenotypes and behaviors for the purpose of mating. These tactics can be genetically encoded and/or arise as a result of plasticity. (A) In Onthophagus nigriventris, major males (right) guard tunnels where females lay eggs, but minor males (left) sneak around guarded tunnels to achieve mating success (photo credit, Doug Emlen).(B) Symphodus ocellatus has three male ARTs. Females prefer the large, colorful, dominant nesting male that provides all parental care (top). Small sneaker males override this preference by sneak mating (bottom). Intermediate-sized satellite males pair up with nesting males and help chase away sneakers but achieve reproductive success by also sneaking (middle, photo credit, Susan Marsh-Rollo). (C) The three male ARTs in Uta stansburiana are maintained through a negative frequency-dependent biological “rock-paper-scissors” game (photos adapted from Corl et al. 2010 with permission from Ammon Corl). (D) When ARTs are state-dependent, the dominant/territorial tactic is only more successful if the individual is in a high enough condition. The fitness curves cross at the switch point where individuals should change tactics. (E) When ARTs are negative frequency-dependent, the expected fitness of a given tactic decreases as the frequency of that tactic increases. The predicted equilibrium frequency of the tactics is where the fitness lines cross (inspired by Figure 1.3 in Oliveira et al. 2008).